According to the adage, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Of course, it depends on the picture (and the words). An image which connects the artist, and by extension, the viewer, to his or her feelings, and provokes the exploration of ideas, is, perhaps worth a thousand words. The relationship between visual symbol and portrayal can be obscure or obvious, and everything in between. A circle may symbolize the cycle of life and death, a shape without beginning or end, and its three-dimensional corollary, a sphere, represents perfection with ancient roots in art and architecture. For example, the Pantheon is defined by the spherical space of its interior.

Telling stories and chronicling events are timeless and universal ways art can persuade, influence, and communicate. I do not consider myself a “social comment” artist, nor do I have much interest in politics but current events such as the separation of families at the Southern Mexico/US border have moved me to create a group of drawings that reflect these events. Inspired by Goya’s Disasters of War etchings and Kathe Kollwitz drawings and prints of the impoverished mothers and children her husband (who was a physician) used to treat in Germany around the time of World War I, I decided to work out some of my own feelings about recent events through drawing. I do not blame or wish to scapegoat any group or organization. Desperation, sorrow, loss, famine, terror, and separation are pervasive themes in the human condition, independent of politics.

Line is expressive in and of itself; in fact, it must be for a drawing to have significance. A line can be tense, scratchy, agitated, sensual, predictable, textured, thick, thin, dark, light, etc. ad infinitum. These qualities, when they correspond to the subject or content bring a dimension of truth to the work that is impossible to arrive at in any other way. This is the nature of an aesthetic experience, a union of the language of the art form with content. The artist organizes his or her response to the subject intuitively in a voice that is appropriate to the meaning of the work.

Rembrandt’s religious etchings are beautiful not only because of what they portray but because of how he tells the story, with love, tenderness, and dignity. Not in an idealized, glamorous way, but in the earthy reality that he saw as divine and beautiful, even with (or perhaps because of), all its imperfections.

These qualities are what make the great history paintings and drawings that chronicle war or symbolize it in allegories so powerful. Picasso’s Guernica, Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa, Delacroix’ Liberty Leading the People and Rubens’ Massacre of the Innocents to name a few. In his haunting etchings “Disasters of War,” Goya chronicles the struggle between the Spanish and French in the Napoleonic Wars with images that disturb, inspire, and enlighten at the same time. The drawings are beautiful, though what they depict is some of the most horrific atrocities men and women have ever inflicted on each other. This work is not decorative, but we must look. Fear, hatred, and brutality are unmasked. We are all capable of inflicting pain on each other. The artist holds up a mirror; it is up to us to look away or face ourselves. The cost of cruelty is high, for both the oppressed and the oppressors.

I find myself repeatedly coming back to the human figure, either literally or symbolically, with its expressive drama, commanding proportions, and pathos, to reveal the relationships between what is outside and what is inside, and to renew the unanswerable questions that each generation must ask itself, not just in order to survive, but to flourish.

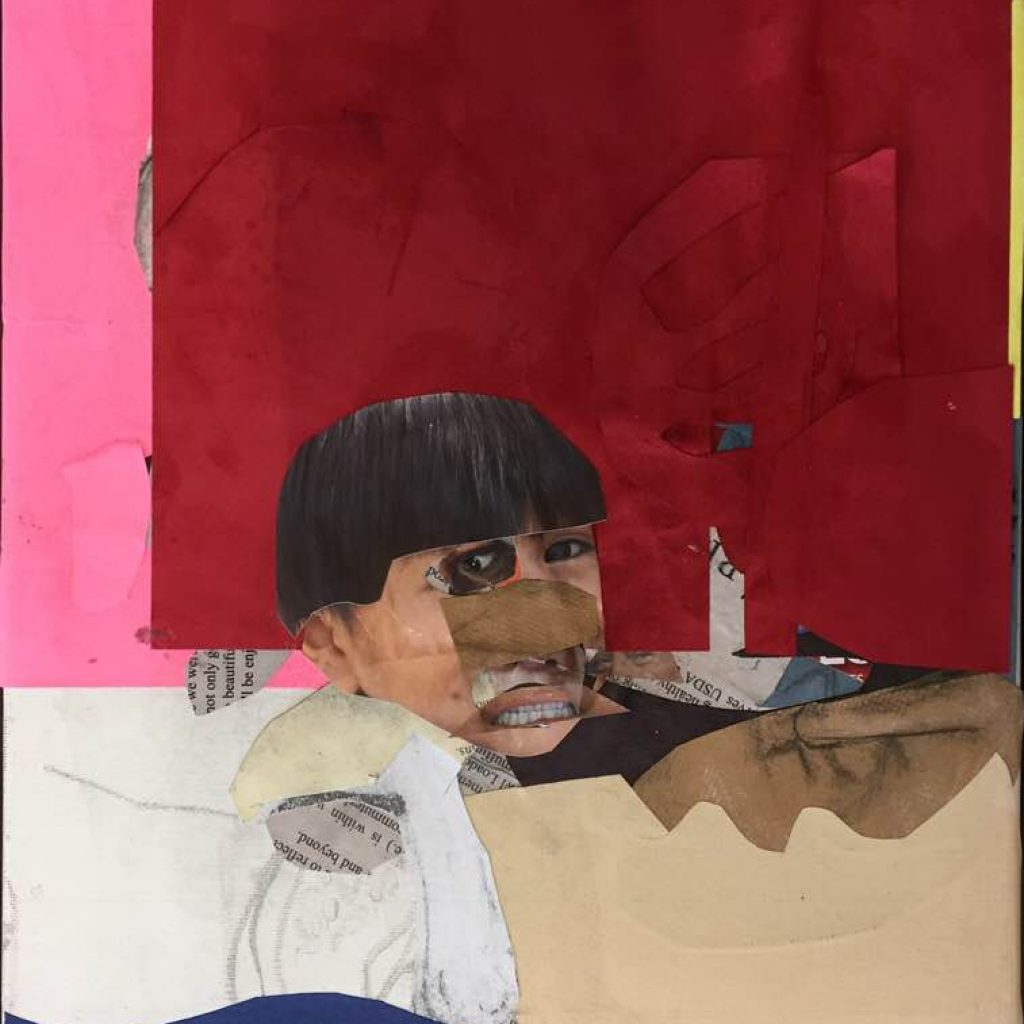

featured image: artist Carol Heft, “separation anxiety” mixed media collage, 11 x 17in

Carol Heft is a New York City based artist and educator. She is a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design and her work has been exhibited internationally. She teaches Drawing, Painting, and Art History at several colleges in New York and Pennsylvania, and is represented by the Blue Mountain Gallery in New York City.